Rhinolophoidea

Nancy B. Simmons and Tenley Conway

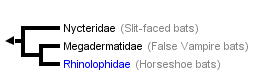

This tree diagram shows the relationships between several groups of organisms.

The root of the current tree connects the organisms featured in this tree to their containing group and the rest of the Tree of Life. The basal branching point in the tree represents the ancestor of the other groups in the tree. This ancestor diversified over time into several descendent subgroups, which are represented as internal nodes and terminal taxa to the right.

You can click on the root to travel down the Tree of Life all the way to the root of all Life, and you can click on the names of descendent subgroups to travel up the Tree of Life all the way to individual species.

For more information on ToL tree formatting, please see Interpreting the Tree or Classification. To learn more about phylogenetic trees, please visit our Phylogenetic Biology pages.

close boxIntroduction

All rhinolophoids are insectivorous or carnivorous, and all are restricted to the Old World. The largest family in the group is Rhinolophidae, which comprises 10 genera and over 130 species (Koopman, 1993). In addition to Rhinolophidae, two other families are included in the superfamily Rhinolophoidea: Nycteridae and Megadermatidae (Simmons, 1998; Simmons and Geisler, 1998). Nycteridae is a small family that includes only 1 genus and fewer than 20 species (Koopman, 1993), while Megadermatidae currently includes 4 extant genera and 5 species (Koopman, 1993). Macroderma gigas, a member of the family Megadermatidae, is the largest microchiropteran bat, with a wing span of 0.6m (Fenton, 1992).

Characteristics

All Rhinolophoidea share the following features:- nasal branches of premaxillae reduced or absent.

- tympanic annulus semivertical in orientation.

- first rib at least twice the width of other ribs.

- first costal cartilage ossified and fused to manubrium.

- m. subclavius originates from first costal cartilage.

- m. omocervicalis originates from transverse process of C2.

- shaft of femur with bend that directs distal shaft dorsally.

- baculum saddle-shaped or slipper-shaped.

Discussion of Phylogenetic Relationships

Many authors recognize Rhinolophidae and Hipposideridae as separate families, but there is overwhelming evidence that these groups are sister taxa (e.g., Pierson, 1986; Simmons, 1998; Simmons and Geisler, 1998; Kirsch et al., in press). Simmons (1998) and Simmons and Geisler (1998) followed Koopman (1993, 1994) in recognizing Hipposiderinae as a subfamily of Rhinolophidae, a nomenclatural arrangement that provides recognition of both the similarities and differences between these clades.

Within Rhinolophoidea, Simmons (1998) and Simmons and Geisler (1998) found strong support for a sister-group relationship between Rhinolophidae and Megadermatidae. This stands in contrast to some previous studies that suggested that Nycteridae and Megadermatidae might be sister-taxa (e.g., Smith, 1976). Monophyly of Nycteridae and Megadermatidae is strongly supported by morphological data (Griffiths, 1994; Simmons, 1998).

References

Fenton, M. B. 1992. Bats. New York: Facts on File, Inc.

Griffiths, T.A. 1994. Phylogeny systematics of the Slit-faced bats (Chrioptera, Nycteridae), based on hyoid and other morpholoyg. American Museum Novitates, 3090:17 pp.

Hill, J.E., and J.D. Smith. 1984. Bats: a natural history. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Kirsch, J. A., J. M. Hutcheon, D. C. Byrnes & B. D. Llyod. In Press. Affinites ad historical zoogeography of the New Zealand Short-tailed bat, Mystacina tuberculata Gray 1843, inferred from DNA-hybridization comparisons. Journal of Mammalian Evolution.

Koopman, K. F. 1983. Order Chiroptera. In Mammal species of the world, a taxonomic and geographic reference, 2nd ed. D. E. Wilson and D. M. Reeder. Washinton, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Koopman, K. F. 1984. Chiroptera: systematics. Handbook of zoology, vol 8, pt. 60. Mammalia, 217 pp.

Pierson, E. D. 1986. Molecular systematics of the Microchiroptera: higher taxon relationships and biogeography. Ph.D. dissertation. University of California, Berkely, California.

Simmons, N. B. 1998. A reappraisal of interfamilial relationships of bats. In Bats: Phylogeny, Morphology, Echolocation and Conservation Biology. T.H. Kunz and P.A. Racey (eds.). Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Simmons, N. B. & J. H. Geisler. 1998. Phylogenetic relationships of Icaronycteris, Archeonycteris, Hassianycteris, and Palaeochiropteryx to extant bat lineages, with comments on the evolution of echolocation and foraging strategies in microchiroptera. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 235:1-182.

Smith, J. D. 1976. Chriopteran evolution. In Biology of bats of the New World family Phyllostomidae, part I. R. J. Baker, J. K. Jones and D. C. carter (eds.). Special Publication. The Museum , Texas-Tech University. vol. 10. Lubbock: Texas Tech Univeristy.

About This Page

Nancy B. Simmons

American Musuem of Natural History, New York, New York, USA

Tenley Conway

University of Toronto at Mississauga, Ontario, Canada

Correspondence regarding this page should be directed to Nancy B. Simmons at

Page copyright © 1997 Nancy B. Simmons

Page: Tree of Life

Rhinolophoidea.

Authored by

Nancy B. Simmons and Tenley Conway.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

Page: Tree of Life

Rhinolophoidea.

Authored by

Nancy B. Simmons and Tenley Conway.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

Citing this page:

Simmons, Nancy B. and Tenley Conway. 1997. Rhinolophoidea. Version 01 January 1997 (under construction). http://tolweb.org/Rhinolophoidea/16091/1997.01.01 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site